Part 1

1. INTRODUCTION

New manufacturing processes developed during the industrial revolution dramatically changed traditional modes of artistic production in the twentieth century. In a culture where the assembly line bred incredible productivity, the object became a commodity subject to the techniques of the industry –the processes of construction defined to contain within it only the most efficient motions. Fragmented to its mechanistic parts, the spiritual object was caught in the motion of the machine and with it, the consumer was enveloped in its bonds. Subverting traditional artistic mediums and processes, artists such as Marcel Duchamp engaged this new relationship from man and object to consumer and product in early twentieth century. Duchamp’s iconoclastic gesture, the “readymade”, satirically commented on the implications of the factory mode operation on artistic production and ensured that the outputs of modern industry would be a fruitful resource for works of art.

The concept of ‘the factory as a site of production’ was arguably conceived by George Maciunas as an aesthetic concept in the sixties coterminously with the concept of ‘multiples’. These notions were explored by Fluxus as well as his contemporary Andy Warhol in conceptualizing the foundation of pop art. Warhol, who was quoted to say that “somebody should be able to do all my paintings for me”, transfigured his studio into a site of factory production while managing his production line of assistants metaphorically as the machines who carried out his work. In the context of his broader mission with Fluxus, Maciunas engaged this concept as a means to work with a world already submerged in consumerism through his political engagement. As a theorist and designer, Maciunas’ functionalism engaged a broader ideological struggle between individual autonomy and loss of freedom emerging from a culture which was to be dominated by the global and the multiple.

In “George Maciunas: Architect”, Ken Friedman states that “Art was a distraction to George. He felt that art distracted the world from what it should be doing. As a result, he felt that he could revolutionize contemporary culture by attacking and overturning the social and economic patterns of art and music”. Within the context of consumer culture, Maciunas gauged these cultural practices within global networks and envisioned complex adaptive solutions for the social collective as an urban planner. As traditional notions of the world as a static mechanism were overturned by scientific discoveries like Einstein’s theory of relativity, few systems existed which could describe those complex, integrative systems. From this ambivalence and uncertainty, individual and collective identities were fashioned in reciprocal motion with the philosophical and social complexities of the modernist epoch. Utilizing ‘art’ beyond the scope of distanced criticism, Maciunas sought to forge a new identity and ethics for man with systems that could cope with a world in a constant state of flux.

——————————————————————————————

2. Origins of Fluxhouse

“Space is a movement in itself, it is never at a standstill, just as the sea is never without a wave. Space is a dynamic force that cannot be defined by static defense, for it is an unconquerable force, which instead of being defined, defines us” –George Maciunas on Le Corbusier

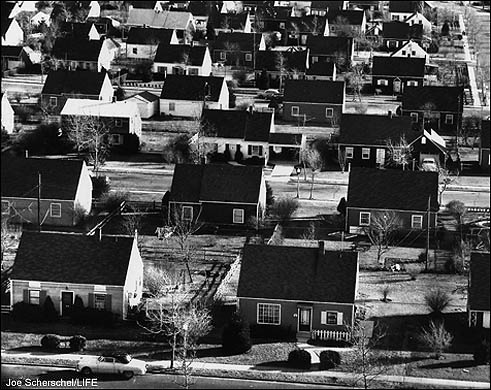

"Aerial view of Levittown, N.Y., c. 1950s" Courtesy of Hofstra University’s Department of Special Collections, Long Island Studies Institute

Levittown

Intended as an improved design to Soviet Block Housing and Levittown, Maciunas sought to offer a resolution to standardized housing which came to resemble a totalitarian nightmare of endless, indistinguishable homes. In the 1978 interview with Larry Miller, Maciunas stated “[functionalism is the way the architect thinks… otherwise he’s not an architect, he’s a sculptor or a stage designer”. His fidelity to functionalism can be viewed in the scientific sense of Occam’s Razor, which in beginning with the fewest assumptions, eliminates what is unnecessary and expresses what is essential.

Themes of economic homelessness, the search for land, and the emergence and transformation of cultural styles were prevalent in Fluxus and throughout Maciunas’ works as an urban planner. Maciunas, who studied the art of European and Siberian migrations for his doctoral thesis in art history at New York University from 1955 to 1959, was likely influenced by the pragmatism of the nomadic tradition. As a precursor to the development of complex civilizations, nomadic dwellings are examples of naturally conceived, efficient designs that act as the most appropriate models for their social, economic, and environmental conditions. In lacking theory or a larger intellectual ordering system for design, these first shelters represent the formative stages for design theory as a traditional, pedagogical way of building.

Silkroad Yurt

In writing ,”for the nomad, ‘home‘ cannot be understood except in terms of journey, just as space is defined by movement”, Labelle Prussin expresses the nomadic ethos as an expression of process without settlement. As it has been expressed that architecture functions as ideology in built form, nomadic concepts of property lend insight into the construction of shelters beyond their material forms and demonstrates a practice of creating living environments through relationships, ideas, and actions. Consonant with Maciunas’ view, ‘homemaking is the greatest of arts’, nomadic ideology is testament to the notion of creating a home and not simply a house.

3. The Static Monument

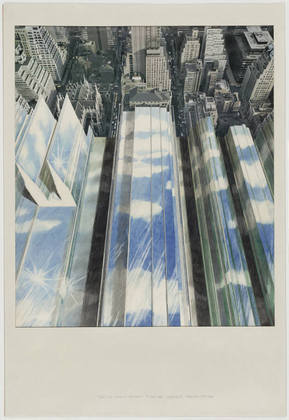

Superstudio, "Continuous Monument" 1969

“If design is merely an inducement to consume, then we must reject design; if architecture is merely the codifying of bourgeois model of ownership and society, then we must reject architecture; if architecture and town planning is merely the formalization of present unjust social divisions, then we must reject town planning and its cities…until all design activities are aimed towards meeting primary needs. Until then, design must disappear. We can live without architecture” –Superstudio founder Adolfo Natalini (1971)

In the context of his era, Maciunas opposed 20th century modernist architects for producing costly and ‘wasteful‘ designs with an aesthetic that conceived the building as a static monument. Treating the high modernism of Wright, Mies, Saarinen and Bunshaft with hostility in “The Grand Frauds of Architecture“, Maciunas perceived the design ideology of these sculptural works of art to serve commercial culture instead of social communities.

Maciunas’ perspective resonates with Superstudio, a collective of architects founded by Adolfo Natalini and Cristiano Toraldo di Francia which was part of the Radical architecture movement of the late sixties. Like Maciunas, Superstudio stated that it is the designer’s responsibility to re-evaluate and refashion the architectural orthodoxies which aggravated the world’s social and environmental problems. Proposing that contemporary culture has become a super-market of anonymous consumption, they proclaimed in “The Continuous Monument” that the only possibility left in this dystopia was monumental extension.

Guggenheim Museum Bilbao

Their relevance is now seen in the ‘Bilbao Effect’: the trend of building trophy monuments to generate profits from tourism and the use of architecture as a signature game. This attempt at urban regeneration was first achieved on a major scale in Bilbao, Spain with the construction of the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao by architect Frank Gehry. With undulating walls of titanium and a 110 million dollar investment, Gehry’s sculptural monument revitalized Bilbao’s economy with an estimated impact on the local economy valued at 168 million Euro in 2011 alone. Despite its economic success, the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao has not integrated into the cultural fabric of its local residents, remaining a sculpturally inspiring but monstrous bombshell. Despite other attempts, all projects have fell short of making such a profitable mark.

Stewart Brand, author of “How Buildings Learn” and producer of a six part BBC series by the same name, examines dramatic and powerful statement buildings which aim to impress observers with flashy facades. In one case, Brand cites how the choice of building materia served a design ideology which defeated the building’s purpose. Glass, a primary building material of the 20th century since the construction of Mies Van Der Rohe’s glass skyscraper in Berlin, met an ill-fated match with spiralling heights in the construction of the tallest skyscraper in New England. This combination in the John Hancock Tower resulted in a building which failed at handling windloads, causing glass panes to fall onto the street and a sway which caused motion sickness to the residents on its upper levels. Upon inspection by Thurliman, a leading expert in high-rise steel buildings, it was additionally discovered that the skyscraper could potentially fall over on its narrow edge with a powerful gust in the right place. Although the structural problems of the John Hancock Tower have been resolved and the building’s blue-tinted glass facade beautifully mirrors the clouds, it reportedly came at an additional cost of $100 million on top of its initial cost of $75 million.

4. Property Bubbles

Interview with DOMUS. Pedro Gadanho, Curator for Contemporary Architecture at the Museum of Modern Art

“Starchitecture is a complex machine that responds to a large-scale global demand. Twenty years ago it would be difficult to imagine. These architects that became stars were great at creating something new and unprecedented, producing an imagination of limitless newness. However, this system also creates expectations of rapid obsolescence… The system eats its own. That’s the system of consumption. It’s no accident that the rise of the star system is parallel to the rise of the consumption system in western society over the last twenty years. In the 1990s and the 2000s, we reached a peak of consumption as individuals.” Pedro Gadanho, Curator for Contemporary Architecture at the Museum of Modern Art

“Henceforth, the Earth could be parceled out, transformed into a commodity, exchanged for money, made subject to financial speculation. In other words, the market-capitalism started its global and solid career… but in the end one has to pay for it” –Dr. Michael Haerdter

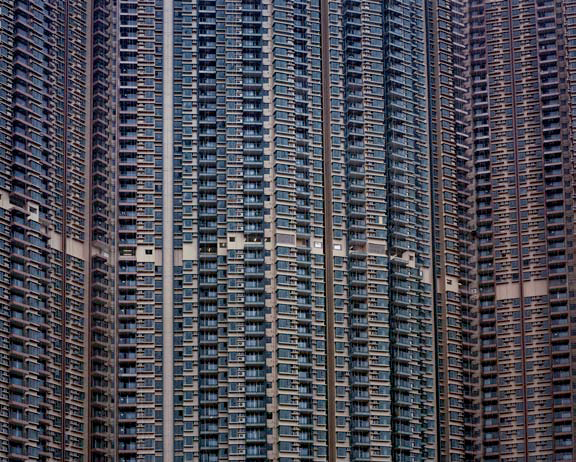

Working in conjunction with developers, real estate speculators, bankers, and government agencies, the ‘star system‘ is related to larger issues regarding property developments played out in real estate bubbles. Characterized by a rapid increase in the valuation of real estate followed by a decline, real estate bubbles develop from a false sense of security based on the high valuation of property which leads people to believe property values will increase over time. In the United States, the burst of the housing bubble led millions of homeowners in possession of mortgages that exceeded the value of their homes and many facing foreclosure. China may currently be facing the history’s largest property bubble as $4 trillion dollars has been invested yet 65 million homes are vacant. With prices continuing to soar, investors have fueled the continued bubble by turning to property speculation.

Prelude XXIV Urban China 2006

“China in particular confronts the western world with the devastating implications of modernity as if in fast-forward. The west is beginning to fear about China what it itself has long since done to the world. In this way, China’s development is the mirror of a western model of progress, and offers a space for anyone to project a bad conscience onto it”. From “Deep Crest and Blooming Garden”, an essay by Professor Johan Frederik Hartle in “Ciphers” by Christoph Gielen

Presenting overwhelming images of urban and suburban sprawl over three continents, Christoph Gielen’s aerial photographs raises critical awareness on Western models of progress for bigger, faster, and ultimately unsustainable growth. In these new morphologies of human settlements, Gielen’s images of sprawl resemble “armor scale structures” more so than human settlements. Rather than humanizing the subject, Gielen’s poetic play between spatial and social development captures the static geometry of these communities, rendering the landscape’s aesthetics into its economic calculations. Dr. Haerdter, in a lecture for NeMe on nomadism, uses Goethe’s “Faust” to describe this sentiment as a triple loss, “The sense of the world’s beauty: the feeling of security; and the loss of happiness, replaced by fear of the future — mainly of losing one’s money and possible profits. (Fischer 2004: 86)”. Gielen’s images of sprawl reflect current trends in which the monetary value of property has trumped its value as human living spaces.

5. Vision Vs Adaptability

“Their statement has very little to do with the actual use of the building. Some architects pride themselves in the fact that their buildings are dysfunctional from the start. There’s a number of American architects who advertise that their buildings don’t work because they’re pieces of art.” Architect Sim Van Der Ryn

The star system is derived from the old modernist notion of gesamtkunstwerk –the environment conceived as a total work of art– to serve as paradises for aesthetes and the wealthy. The emergence of these structures also gave rise to ‘starchitects’, architects who have achieved celebrity status for their lyric buildings. Reflected in Le Corbusier’s narcissistic statement that people should adapt their lives to suit his modernist designs, these conceptions reflect a shift from the architect as craftsman to the architect as artist.

With the deliberate destruction of the traditional built environment by the modernists, the built form was no longer based on human sensibilities. Meant to provoke psychological and physiological anxiety in the observer, the abstract criteria of their raison d’etre frequently obstructed the relationship between human beings and their milieu by intentionally breaking up space and form. Its effects are clearly stated by architect Max Hunt, “When a building is friendly, you can do a lot of good business. When a building is terrible, people will always be ill”.

Looking across a spectrum of historic and modern structures, Stewart Brand makes a distinction between visionary design which conceives of the building as art and evolutionary design which accounts for emerging needs to shape form and function. In a notion shared by architectural theorist Christopher Alexander, Brand states that the main architect to some of the most successful structures and designs is time. In this respect, he considers the construction, maintenance, and renovation of a building as important aspects to consider in a design process.

Pallazzo Pubblico. Siena, Italy Built over 500 years, this beloved public is an example of evolutionary design

In this study of how designs change, Brand cites the beloved Palazzo Pubblico in Siena, Italy as an instance in which form beautifully met with function. Also seen in gothic cathedrals, additions such as a spire, medici arms, crenelated tower, and belfry were integrated to this public space over five hundred years. As a solution to the disparity between vision and sensibility, Brand encourages a view of architecture as a creative process rather than product in valuing adaptable living spaces over impressive first impressions.

Part 2

6. Low-Road Buildings and Fluxhouse

“temporary is permanent and permanent is temporary”–Stewart Brand

Evolutionary design is married with economic efficiency in what Brand calls ‘low-road‘ buildings: low visibility, low-rent, no-style, high turnover structures. As these buildings are free of “turf battles because the tuf isn’t worth fighting for”, he states these buildings are valuable precisely because they are inexpensive, thus promoting growth and shifting the value to the work and functions which take place inside. Citing a nobel physicist who stated, “we did some of our best work in the trailers, didn’t we?”, Brand suggests that these spaces are conducive to a creative spirit because projects flourish in low supervision environments.

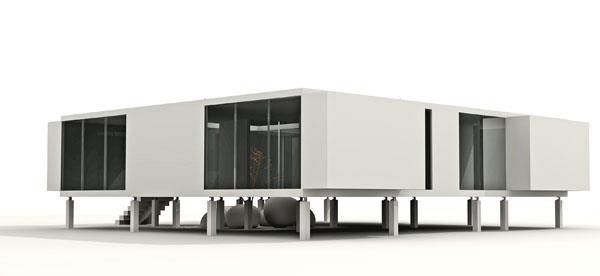

Modular prototype

Consonant with Fluxhouse, Brand states that a supply of simple, low-cost, easily modified buildings based on an organic design and process of building is essential for social and economic growth. Brand values an organic design and process of building based on four walls which can easily expand and grow as its ideal design. Though Fluxhouse is a prefabricated unit, Maciunas conceived of this modular design as a structure built for adaptation in stating that the design can be customized to residential, institutional, industrial, or agricultural functions, and units can be multiplied to create a single family home, mid-rise building, or a city. Maciunas, who stated “efficiency is giving the most performance for the least cost“, conceived of Fluxhouse as a mass-produced design for the sake of cost efficiency. As high level of production could allow for low cost with much of the production occurring in the factory, Maciunas considered prefabrication as an innovative cost and time effective solution to the process of construction.

Fluxhouse. zen courtyard

Like Brand, Maciunas considered construction, maintenance, and renovation as part of a design process which corresponds to the building’s growth and evolution. His consideration to sustainability is reflected in this eco-friendly design resistant to natural disasters including fires, floods, earthquakes, and hurricanes, as well as deterioration caused by rot, termites, corrosion, and discoloration. Multi-functional and cost-efficient, Fluxhouse demonstrates an ideology which values organic usage over visual theatrics as a mass housing system designed to be sustainable in its production, construction, and use.

7. Fluxhouse Cooperatives

“It makes me vomit the way local developers have started moving in and buying up large buildings. The problem is that the sort of people that are buying them can afford to pay the commercial rates for the pleasure of being in there and so its distorting the market terribly. The thing about areas anywhere in the world and any time where artists have moved in to, the reason why they move into these areas is because spaces are cheap. It would be a very unfortunate thing if this community was broken up by developers selling these spaces off to people who have more money than sense.” –Artist Brad Lochore

In the case of low-road industrial buildings, Brand notes instances in which artists have seized the potential of cheap, well-built, and spacious buildings. As artists move into an industrial neighborhood and creatively renovate the buildings into live-work studios, trendy restaurants and shops move in and transform the neighborhood into a fashionable place to live. Antithetically, the process stops when developers move in and convert the studios into upscale apartments which raises prices and forces artists out.

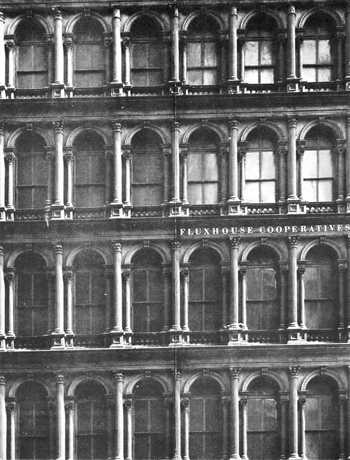

Fluxhouse Cooperatives

As an urban planner, Maciunas is credited as the “Father of SoHo” for converting industrial loft buildings with artists’ cooperatives known as the Fluxhouse Cooperatives during the late sixties. Like other Fluxus works, Maciunas managed his duties without personal profit. With a grant from the J.M. Kaplan Foundation and the Federal Housing Administration, Maciunas challenged New York City’s M-1 zoning laws to construct the Lower Manhattan Expressway. Conceived by the controversial urban planner Robert Moses, the LME was a vast highway which would have obliterated much of lower Manhattan’s industrial loft district.

Lower Manhattan Expressway (unbuilt)

Though Moses was opposed by dozens of public figures and over 200 community groups, the loft artists’ power effectively stopped Moses: “Opposition to the expressway was going nowhere. Our whole planning board couldn’t even slow it down. Then a handful of artists stepped in a stopped it cold” (South Houston Artist Tenants Association). With the Fluxhouse Cooperatives, Maciunas played a fundamental role in revitalizing SoHo from its condition as a dilapidated post-industrial site and centralized this area as an enclave in which Fluxus’ neighboring movements have flourished.

The Fluxhouse cooperatives were indicative of Maciunas’ broader views as a social planner in conceiving the community through cooperative living arrangements. Rather than expressing personal artistic-intuitive caprices, Maciunas’ corpus of work reflects a search to develop a social and economic dynamic relevant to the built environment and the condition of its social body. Maciunas’ work as an architect, urban designer, and Fluxus coordinator reflects the same ideal of decommodifying and deaestheticizing art in order to merge art with the realities of the concrete world. Like Brand, who described low-road buildings as “genuinely empowering”, Maciunas valued efficient ad hoc design with materials at hand. His “do-it-yourself” aesthetic reflected his goal to turn everyone into an active and knowledgeable participant rather than passive observer. Perceiving Fluxus as “a way of living”, Maciunas’ ‘art’ works was directed towards improving the social milieu by creating the appropriate conditions for a successful community.

As a collectivist, Maciunas’ aesthetic ideology is grounded in ethical concerns of the social condition produced by a consumer culture. As opposed to a unitary vision of the subject, Utrecht Professor Rosi Braidotti states that complex, split, and nomadic conception of the subject constitutes a necessary precondition in considering a global model of ethical practice. Professor Braidotti states that the reciprocality of Kantian or Christian-Judeo morality of “I do that for you, you do that for me” is insufficient as a capitalist driven negotiation of boundaries unable to address ethics on a global scale:

“No! You do that for the love of humanity, because if we don’t do that, there is no going to be a humanity! … And we have to give up a certain notion which, by the year 2010, has lead to an assimilation of progress with further consumption: you will consume more than we did, we consume more than our parents did, our parents consumed more than their parents did… as a consequence of that, now we are at the verge of a catastrophe, financial, environmental, demographic.” Rosi Braidotti

——————————————————————————————

8. Collective Intelligence & Emergence

Maciunas’ collectivist sensibility is consonant with the notion that complex organization emerges from the multiple actions of its dynamic components, materializing the effects of countless simultaneous preferences, choices and actions.Fluxcity was Maciunas’ expression of what has recently been developed as ‘smart-cities‘ derived from studies into advanced communication and storage infrastructure.

Illustrated in the superimposed and transparent maps of the “Atlas of Russian History“, adaptive design is grounded in the notion that the organic evolution of many agencies leads to the development of dramatic and beautiful complexity. In “Design Methods, Emergence, and Collective Intelligence“, mathematician Nikos Salingaros describes this cathartic experience as emergence. Salingaros identifies its properties with information, meaning, learning, and connective subsystems to describe it as “a unity that takes on a ‘life’ of its own”. Understood in past centuries in religious terms as the ecstatic experience naturally associated with a great structure, emergence is analogous to the notion that a whole is more than a sum of its parts as its beautiful quality is an expression of collective empathy and belonging.

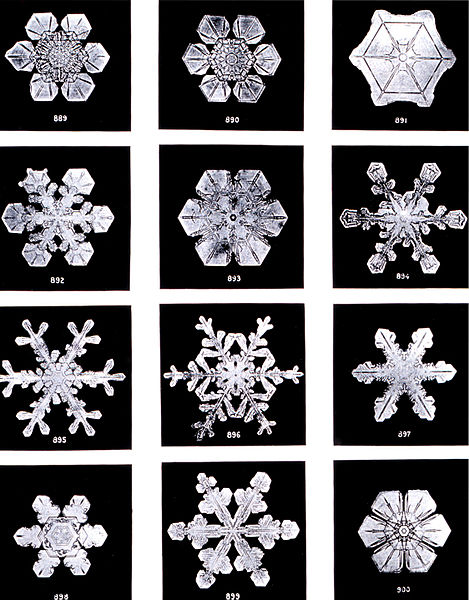

Snowflakes forming complex symmetrical patterns is an example of emergence in a physical system

Manifested from the fabric of cultural memory, emergence is analogous to the notion that a whole is more than a sum of its parts. While Salingaros writes that individuals have an advanced capacity for intelligence, he states it is necessary at times to use a combination of minds in order to generate complex mechanisms. As traditional, adaptive ways of building were destroyed by the modernists, Salingaros argues that human intelligence could no longer be extended to the built environment.

Prescribing collaboration to regenerate collective intelligence, Maciunas’ architectural and urban works demonstrate adaptability and flexibility as prime strategies to cope with the nascent instabilities of the world. His atlases, charts, and diagrams are expressions of intelligent systems which can effectively deal with a mass-produced and global culture. In developing learning models, his views as a social planner demonstrate knowledge-based economies in collaborative networks. As a means to overcome the problems of early specialization and fragmentation, these networked conceptions of human relationships reflect the emergence of collective intelligence in a social body.

9. Learning Machine

“Any dynamic complex system, if it is able to do so, will try to organize its complexity as to optimize energy flow. This response or self-organization can be interpreted as a kind of ‘learning’, though it is not always in directions that human beings either approve of or understand.” –Nikos Salingaros

Turing Machine

Learning Machine

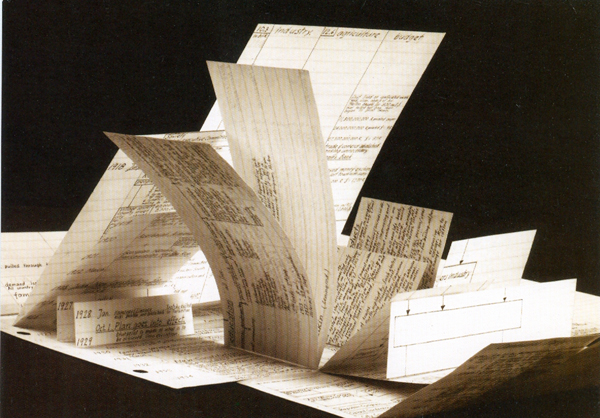

By continuous interaction and dialogue, adaptive solutions demonstrate learning processes. Prevalent throughout his corpus of work, Learning and education were primary themes throughout Maciunas’ corpus of work. Regarded by Maciunas as his best work, “Learning Machine” is an unrealized, conceptual model like the Turing Machine conceptualized by mathematician Alan Turing in 1936. Frequently mentioned in philosophical discourse on artificial intelligence, Turing conceived of the machine as a model for computation thus creating the origin of the stored computer program.

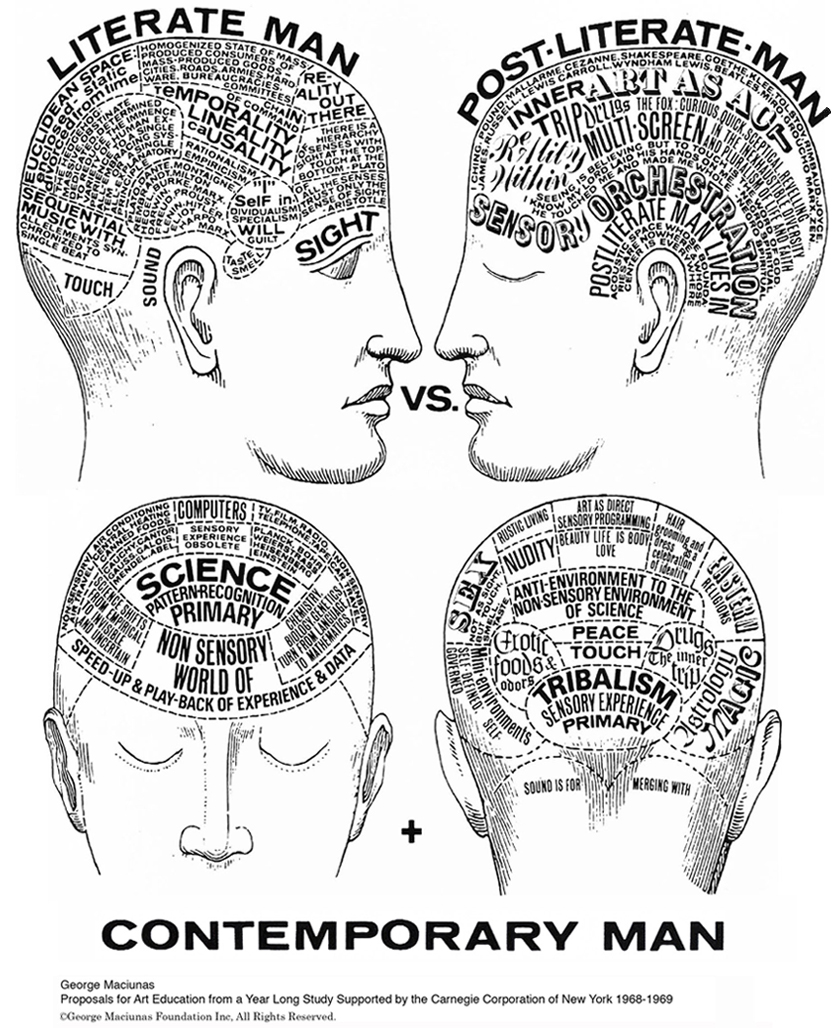

Contemporary Man

Reflecting networked processes, Maciunas’ “Learning Machine represents the transcendence of knowledge processing from two dimensions to multi-dimensional modes. As an model of global, contextual knowledge, the “Learning Machine” expresses the manifestation of emergence of human thought processes in the post-modernist epoch. Also reflected in the cranial diagrams of “Contemporary Man”, the “Learning Machine” demonstrates a shift in the Western mentality from linear, sight-based paradigms to symphonic, non-sequential modes of understanding. Rendering emergence in diagrammatic form, Maciunas depicts the morphogenesis of the Western paradigms from its simpler patterns of knowledge processing.

As a social housing system, Maciunas intended the flexible nature of Fluxcity to create new urban morphologies based on the motion of daily life and the needs of the city. Prescriptive rather than visionary, Maciunas diagnosed the pathologies of mass-housing through reconceptualization of its unit and the patterns into which it may evolve. Like the transcendence of knowledge in “Learning Machine”, Fluxcity imitates the process by which unstructured networks like the internet have manifested structure through the collective intelligence of its users and designers. Achieved through total cost-efficiency by factory production, the aesthetic ideology of Fluxcity demonstrates the potential to cultivate infinite possibilities for different ‘programs’ as an urban solution.

10. THE MODERN URBANIZATION OF FLUXCITY

“Efficiency is giving the most performance for the least cost”– George Maciunas

In current socio-economic trends, contemporary conceptions of Fluxcity may be realized through the construction of a ‘green’ city. Maciunas’ philosophy of complete economic efficiency is feasible with self-sustainable methods achieved by an economical construction process and urban design solutions which promote low running costs to maintain the city. In promoting the condition in which economic freedom spurs high levels of innovation and creativity, Maciunas’ conception of Fluxhouse is consonant with the notion that property is inexpensive and the work taking place inside is valuable. Achieved by mass production, Fluxcity holds its greatest potential as a quick and affordable solution to a host of pressing social housing problems.

Slum

Tent city in US

Realized on a global scale, Fluxcity may be used as a social housing system to urgent situations such as shantytowns. As the world’s fastest growing urban habitat, slums are areas that exist outside of an official city grid and lack safe water and sanitation, public services, basic infrastructure, and quality housing. According to the UN News Center, the number of people residing in these slums have risen from 777 million in 2000 to 830 million in 2010. The number is expected to rise to 900 million in 2020 unless drastic action is taken. In the United States, tent-cities have cropped up across the country from Seattle, Washington to Athens, Georgia since the foreclosure crisis began in 2007. With these modern day Hoovervilles, homeless advocacy groups and city agencies have reported the most visible rise in homeless encampments in a generation.

Christoph Gielen "Untitled IV" Arizona 2010

Fluxcity may also be used to resolve urban and suburban sprawl in the United States by creating infrastructure and improving quality of life as a social project. Achieved on a national scale, the construction of a new housing project may stimulate the economy and improve the social fabric of communities. The last project of this scale was achieved by Robert Moses, who dramatically changed American culture by building highways, bridges, and parks in New York in the mid twentieth century. As the shaper of the modern city, his philosophy for a car based culture influenced urban planners across the country and has precipitated the decline of public transportation while producing greater greenhouse emissions.

In the context of the current economic depression, relief for the lower and middle class may be achieved through grand scale national economic programs like Roosevelt’s New Deal. Shifting from a consumer system of cars and single family houses towards community based urban designs may be a step toward resolving many of the country’s social, economic, and ecological issues. As a federally sponsored solution, Fluxcity would gentrify communities while creating jobs, thus acting as a triple solution in amending housing crises, resolving unemployment, and generating social welfare.